Why Britain Fell Behind, Part 2: Measuring Decline

Let's Measure

This is Part 2 of an extended essay. Click here for Part 1 (Intro/Index).

Measuring Decline

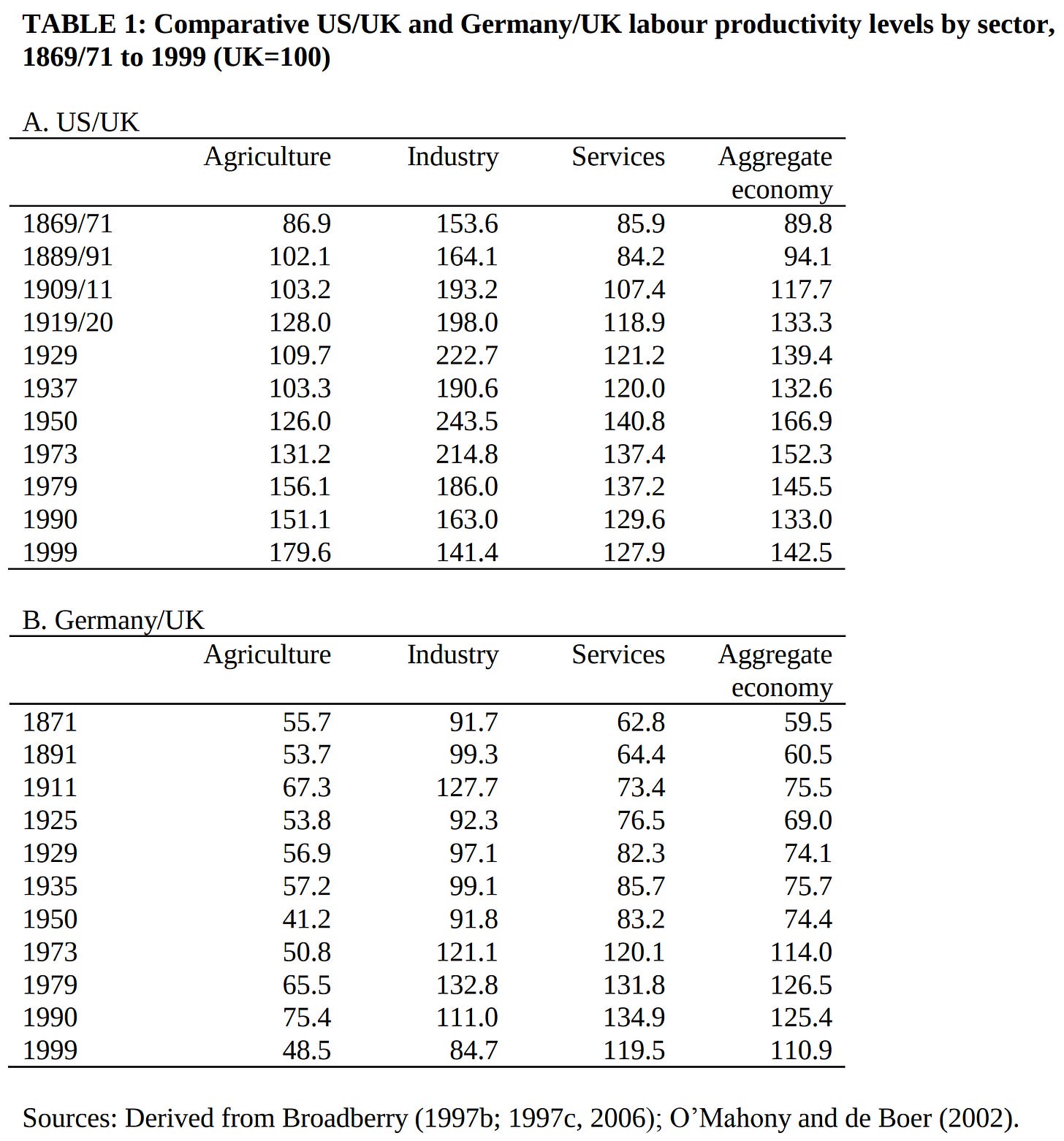

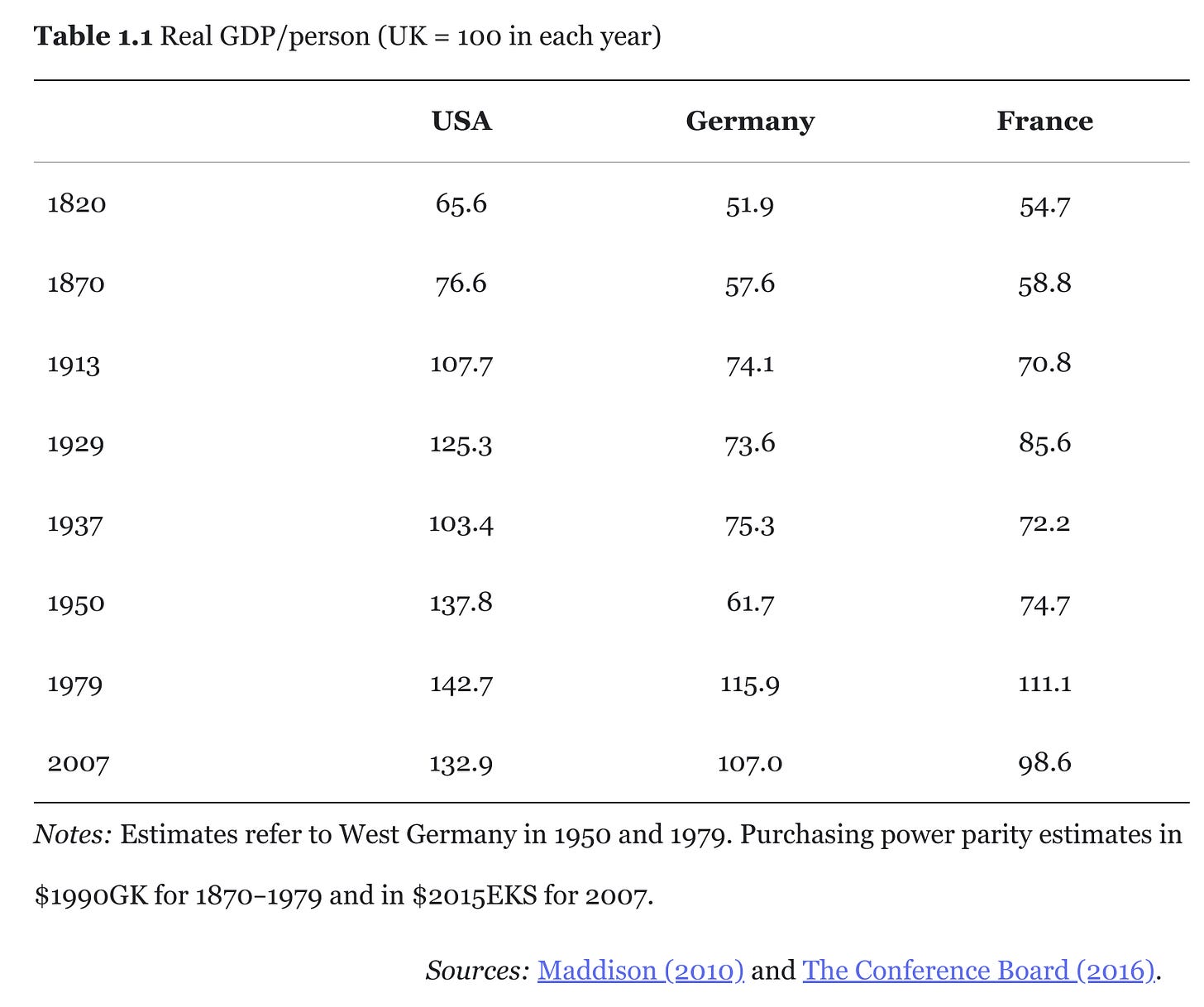

To begin with, we must understand the extent of Britain’s failure. Britain really did fall behind, but perhaps not as far as one would expect. There is varying data for this, but the numbers provided by the late economic historian Nicholas Crafts are as good as any. He tabulates that Britain started out in 1950 richer than France and West Germany and finished in 1979 poorer than them both, with a gap of around 15% in GDP per capita adjusted for inflation and Purchasing Power Parity.

A 15% gap doesn’t sound big. It certainly does not match the often histrionic rhetoric of British decline, especially given that Britain as a whole got richer throughout this period. But there are a few important caveats to this.

Firstly, these are PPP-adjusted terms. The nominal GDP numbers often looked much worse, and they were the figures used as the points of comparison at the time1. On these metrics, the UK was, in terms of both per capita and total nominal GDP, behind not only Japan and West Germany but also countries like France and even Italy at one point, nations the British had traditionally thought of as “nice guys, but poorer”.

Secondly, and related to this, was the perennial weakness of Britain’s currency. The UK suffered several humiliating sterling crises in the postwar years and eventually became plagued with high inflation, a painful contrast to the trade surpluses and rock-hard Deutschmark possessed by West Germany. Then, as now, the strength of sterling was treated as a test of national virility rather than a macroeconomic variable.

Thirdly, Britain’s productivity (data for which is provided below) was often worse than its PPP-adjusted GDP per capita might suggest, with the difference accounted for by Britain having more working hours per inhabitant. This naturally had a negative impact on wage rates and living standards. It is also a problem that the UK has never fully shaken off, even in the ‘90s and ‘00s.

Finally, the problems of the British economy were heavily concentrated in manufacturing, which was the most tangible part of the British economy for most people. The failings of sectors like steel or (most infamously) automobiles were painfully evident to all, with vivid imagery of factories closed and national champions lost forever. Success in other fields (especially services) tended to remain under the radar (how many people know what PwC is?).

All this meant the travails of the British economy felt like (and arguably were, given the extent of the underlying problems) a far greater crisis than falling behind by 15% in PPP terms might suggest, hence the endless discourse of British decline at home and abroad.

And even then, there was no inherent reason why the UK had to fall behind in the first place. After all, the US had emerged from WW2 as the world’s richest major economy and has retained that crown ever since. Why couldn’t Britain be an economic titan ala West Germany, or at least keep pace with its funhouse mirror twin, France?

To understand, we have to go back to the beginning.

Paradise Lost?

What made Britain such a leader in the first half of the 20th century? If we zoom out from the industrial minutia and take a look at the British economy in broader scopes the answer becomes clear. Britain’s lead was built not on industrial efficiency—the Americans were the uncontested pacesetters in that regard—but on the unusually mature structure of its economy.

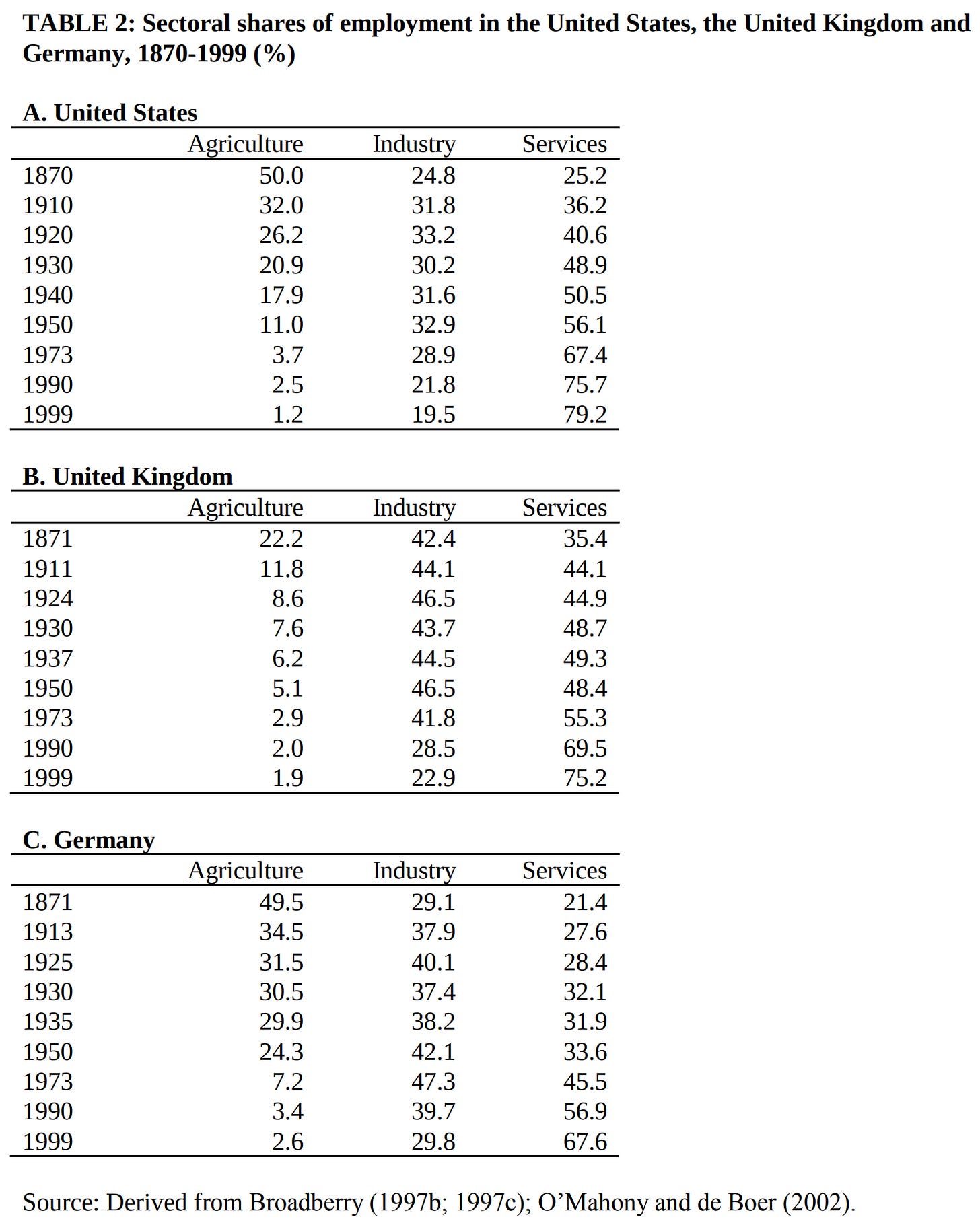

British industry was roughly as productive as its German counterpart (although both countries were far behind the US). The real difference lay in the agricultural sector. Britain—the home of the industrial revolution and the world's most urbanised country bar a few city states—had a small and productive agricultural sector that by 1950 employed merely 5% of the workforce. By contrast, Germany that year had nearly a quarter of its workforce employed as essentially peasant farmers in a backwards agricultural sector, and the numbers before 1950 were even more drastic.

This difference was a major factor in WW2. Throughout the war, the British Army was fully motorised, a stark contrast to the French and German armies, most of which were un-motorised infantry using horse-and-cart for transport.

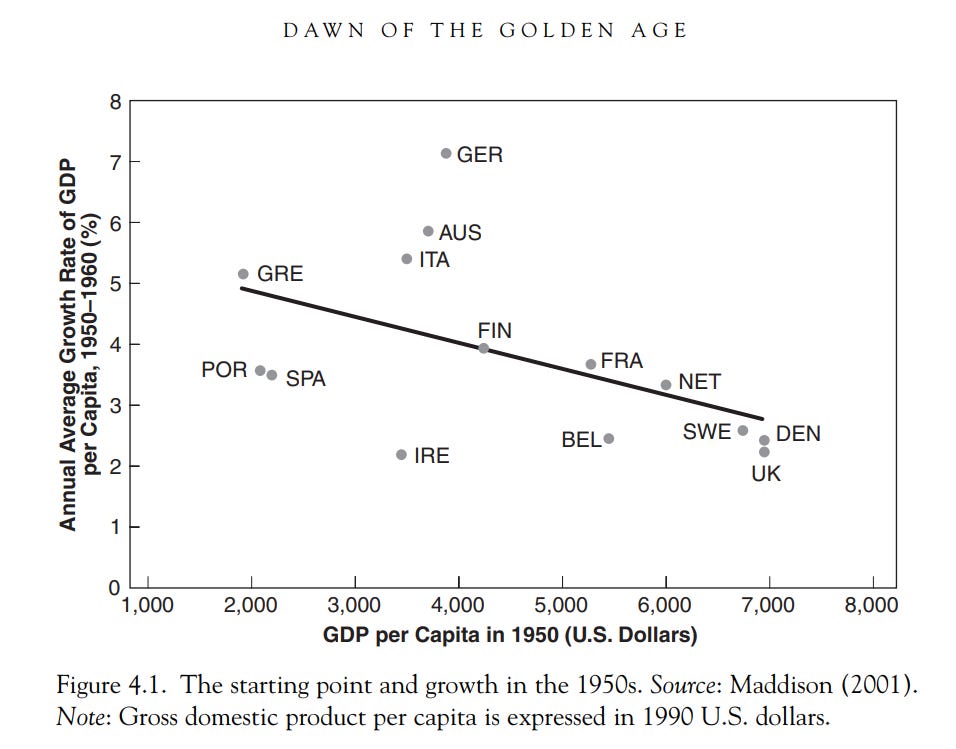

What was true for Germany was also true to varying degrees for almost every other country in Europe and Japan. These countries were able to grow rapidly after the war by moving labour out of the agricultural sector and into industry and services, undergoing the kind of industrialization and urbanization that Britain had already experienced. This alone explains most of why the UK grew more slowly than its continental counterparts.

This is the Anti-Declinist thesis in a nutshell: Britain grew slower because it was richer and more developed, mystery solved.

But I don’t find this a satisfactory explanation. Yes, the British economy was always going to grow slower than that of West Germany, France, or Japan. But it was not inevitable that it would be overtaken by them. Nor was it inevitable that British industry, in particular, would suffer such a dramatic fall from grace.

Part 3, “The Good, The Bad, and the Attlee”, will be available soonish.

PPP figures were not widely used at the time. Additionally, nominal figures are a better measure of a country’s economic heft in international terms, which is what many pundits and politicians cared about.

Isn't this proof that the UK productivity is worse than USA, Germany and France? Why does the population per sector matter?

Well, the first challenge is defining what you mean by "decline"; over the decline years, typical Britons experienced a transformation of their lives in terms of consumption while also gaining a comprehensive welfare state, after all. This quote makes the point:

"The failings of sectors like steel or (most infamously) automobiles were painfully evident to all, with vivid imagery of factories closed and national champions lost forever. Success in other fields (especially services) tended to remain under the radar"

Here, we're plainly talking about the 1980s, but decline discourse was already flourishing when the industrial share of GDP was actually <em>rising</em> and e.g. English Electric was simultaneously making power stations, electric railways, trains to run on them, fighter jets, and computers.

I can think of a <em>lot</em> of different definitions:

- economic growth was fast in 1945-1975, but not as fast as country x

- productivity growth was fast in 1945-1975, but not as fast as country x

- the US and USSR, or today, China, are more powerful in political terms than we are

- countries in the empire want to be independent (remember that depending where you stood in politics you might think this was either treachery, pragmatism, or a desirable goal of policy)

- traditional industries are collapsing post 1981 (or the oil crisis)

- kids these days, don't know if they're arthur or martha, what with them pop singers etc etc

- my social class is no longer as rich or powerful relatively as it used to be (obviously this was often a desirable goal for the other social classes, who considered it progress rather than decline, and taken together, it's just a statement that the great compression was a thing and you wish r would be > g again)

- general yadda-ing about whatever culture trend doesn't agree with your tastes

- prejudices of various kinds

As a lot of these are mutually exclusive, and some of them are just bullshit, you need to pick among them and stick with your choice. This also implies answering questions like "decline, for who?" - I am sure if you had to let the hoi polloi visit the country seat because r < g and the taxes are up, and you weren't going to personally rule half of India, you were pretty sure that was decline, but not being a country squire I don't see it that way.

Alternatively you can go with a higher-order approach and ask why, despite the fact that one man's decline was so often another's progress, so many people agreed on decline as a general kind of vibe, but then that's going to involve a lot of vague culturalist waffling.