The Fall of France (aka the Battle of France) is usually brushed over in histories of the Second World War. It is treated as an inevitability, the bit we must skip over to get to Churchill and the finest hour of the Battle of Britain. Perhaps for this reason, there is little reflection on this event 85 years on. Even in France, it is overshadowed by the torment of what came afterwards.

This is a great mistake. What happened in 1940 was not inevitable; it was extremely contingent. And far from being a historical footnote, it is one of the most consequential events in history. Without it, the modern world would be radically different. In so many ways, we live in the aftermath of 1940.

An Avoidable Disaster

The Fall of France was far from preordained. Yes, Britain and France had failed to rearm properly. Though, for Britain in particular, the problem wasn’t so much that it hadn’t rearmed enough as that it had spent the money on the wrong things (vast sums were poured into a Bomber Command that was almost totally ineffective, whilst Fighter Command and above all the British Army were neglected). The British and French had significant doctrinal problems, particularly involving the coordination of air and ground forces (though the much maligned methodical battle doctrine wasn’t as dated as is commonly said). The Maginot Line was probably a waste of money (but so was the Siegfried Line), albeit not for the commonly cited reasons.1

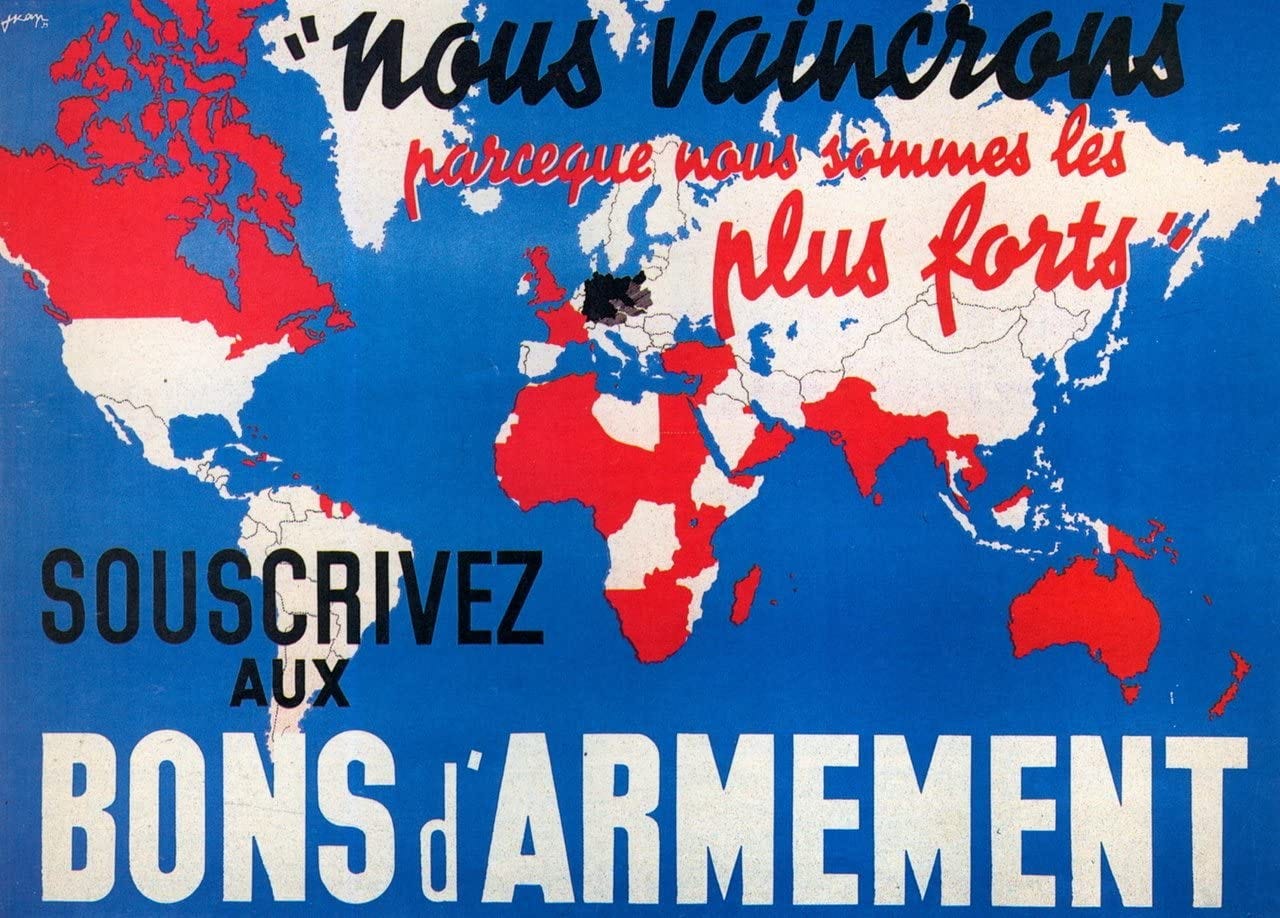

But despite all this, Britain and France had what was needed to inflict a shattering defeat on Germany. They had the necessary, albeit not exemplary, equipment (e.g., France had more and heavier armoured tanks than Germany did), and the German attack would present an orchard of ripe opportunities. Crucially, the economic superiority of the British Empire and the French Republic—augmented by the large purchases from the United States under the cash-and-carry system—was so vast that, in the long run, a German defeat was inevitable.2 In fact, we now know that the German war economy was in a very precarious position that was only stabilized by the systemic looting enabled by the Fall of France3. This stark reality even drove some German generals to consider assassinating Hitler.4

So why did they lose? The primary failure was an operational one. The French Army did not anticipate that the German armour would come barreling through the Ardennes Forest (thought to be a stronger natural barrier than it actually was and thus guarded by third-rate units), and botched its counterattack when they did. Whilst the bulk of British and French forces raced into Belgium to meet a diversionary German attack, the actual German thrust sliced through allied lines at their pivot point, and then swung north to encircle the large allied force that had moved into Belgium.

It’s hard to overstate how extremely risky this maneuver was for the Germans. It would have only taken a few different decisions, before or during the battle, for it to have become a catastrophe for the Wehrmacht.

Allied reconnaissance aircraft actually spotted the huge traffic jam created by German forces lining up behind the Ardennes, but Allied high command disbelieved it. Had they believed the reports, they could have counterattacked early and halted the German thrust in its tracks.

If the French counterattack at Sedan had succeeded, it could have disrupted the German advance midstream.

If the Allies had kept some more reserves instead of committing so heavily to Belgium, they’d have had a range of options to counter the German assault.

Etc, etc, etc.

Germany effectively rolled double sixes in 1940.

The Consequences

It’s hard to overstate how consequential this all was. The historian David Reynolds once described 1940 as the “fulcrum of the 20th century”; the Fall of France was its linchpin.

This can perhaps be best illustrated by imagining how history would have been if 1940 had gone the other way. Alternate history is beloved by armchair commentators but treated with scepticism by academic historians. I’m the former, so indulge me with this educated conjecture.

Germany would be defeated by Britain and France, perhaps as early as 1942. Anglo-French economic superiority ensured that. This would still be bloody — the Anglo-French would have to do the hard yards of grinding down the Wehrmacht in a land campaign as the Red Army did in our world. But it would happen. Europe would be liberated by Europeans.

There would be no Eastern Front as a result. The USSR would have been spared the trauma of losing 27 million of its citizens, and Eastern Europe would not have fallen under Communist suzerainty. This, in turn, means no Cold War as we know it and certainly no bipolar postwar world.

Nor would there be a Mediterranean Campaign; Mussolini's regime could remain in power for as long as Franco’s did.

There would be no Pacific War as we know it. No Fall of France ➔ no Japanese occupation of Indochina ➔ no American oil embargo that laid the powder trail to Pearl Harbor. And with Italy out of the fight, the Royal Navy and Marine Nationale would be free to deploy a large naval force to the Far East.

Europe would be far richer and more powerful as a result. A vast amount of damage, death, and indebtedness would be avoided. The Holocaust would have been interrupted midstream. European integration would still have occurred, but it would have taken a different form. Britain and France, in particular, would be far stronger economically, militarily, and politically. For good or for worse, their Empires would have lasted longer and their influence would be stronger.

The United States would remain largely confined to the Western Hemisphere, with no WW2 or Cold War to drag it out of its isolationist shell. The idea that the US would be the world policeman and the security guarantor of Europe and the Middle East would be seen as an absurd fantasy.

Still in the Shadow

The latter point is especially pertinent today. The Fall of France ensured that Europe would not be liberated without the intervention of the outside powers, the US and the USSR. 85 years later, Europe still depends on one of those powers to defend it from the remnants of the other. Only recently has Europe, belatedly, begun to recover its strategic independence.

Donald Trump’s present-day assault on the American republic and its alliance network is indeed shocking, especially from a European point of view. But it should also be shocking that, after all these decades, Europe still relies on the United States to be its military guardian.

That would have been inconceivable without the Fall of France.

If you received this post twice, I apologize, as I’ve been experimenting with the send features.

The book Case Red by Robert Forczyk is a fascinating source for all this.

Hence their “Assurance of Victory,” to quote David Edgerton’s book Britain’s War Machine, which covers this issue.

Adam Tooze’s book The Wages of Destruction covers this in detail.

See The Wages of Destruction by Adam Tooze, Chapter 10.

Even before that, if the Allies had acted when Hitler reoccupied the Rhineland.

Stalin would have still moved on Eastern Europe/Germany? After that the rest of the counter factual collapses?